You need $2-5 million to hit your next growth milestone, but giving up 25% equity in a Series B feels premature. This is where venture debt becomes an attractive option, but it comes with its own unique terms, specifically, warrants.

So, what are they? And more importantly, how much of your company are you really giving up?

This guide breaks down how venture debt warrants work, what to expect, how to measure the risk, and what it means for your cap table.

A warrant gives a lender the right, but not the obligation, to buy a specific number of your company’s shares at a preset price (the “strike price”) before a set expiration date.

Think of it as a long-term stock option for the lender. They provide the loan, and in return, they get a chance to share in your company’s future success. If your company’s value grows, they can exercise the warrant, buy shares at the original, lower price, and see a return. If not, the warrant expires worthless, and they are not required to do anything.

Most warrants last 5-10 years.

Lenders use warrants to balance their risk and reward. Unlike equity investors, a debt lender’s primary return comes from interest payments. Their upside is capped. Warrants give them a small piece of equity potential to compensate for the risk they take on, especially with high-growth, pre-profitability tech companies.

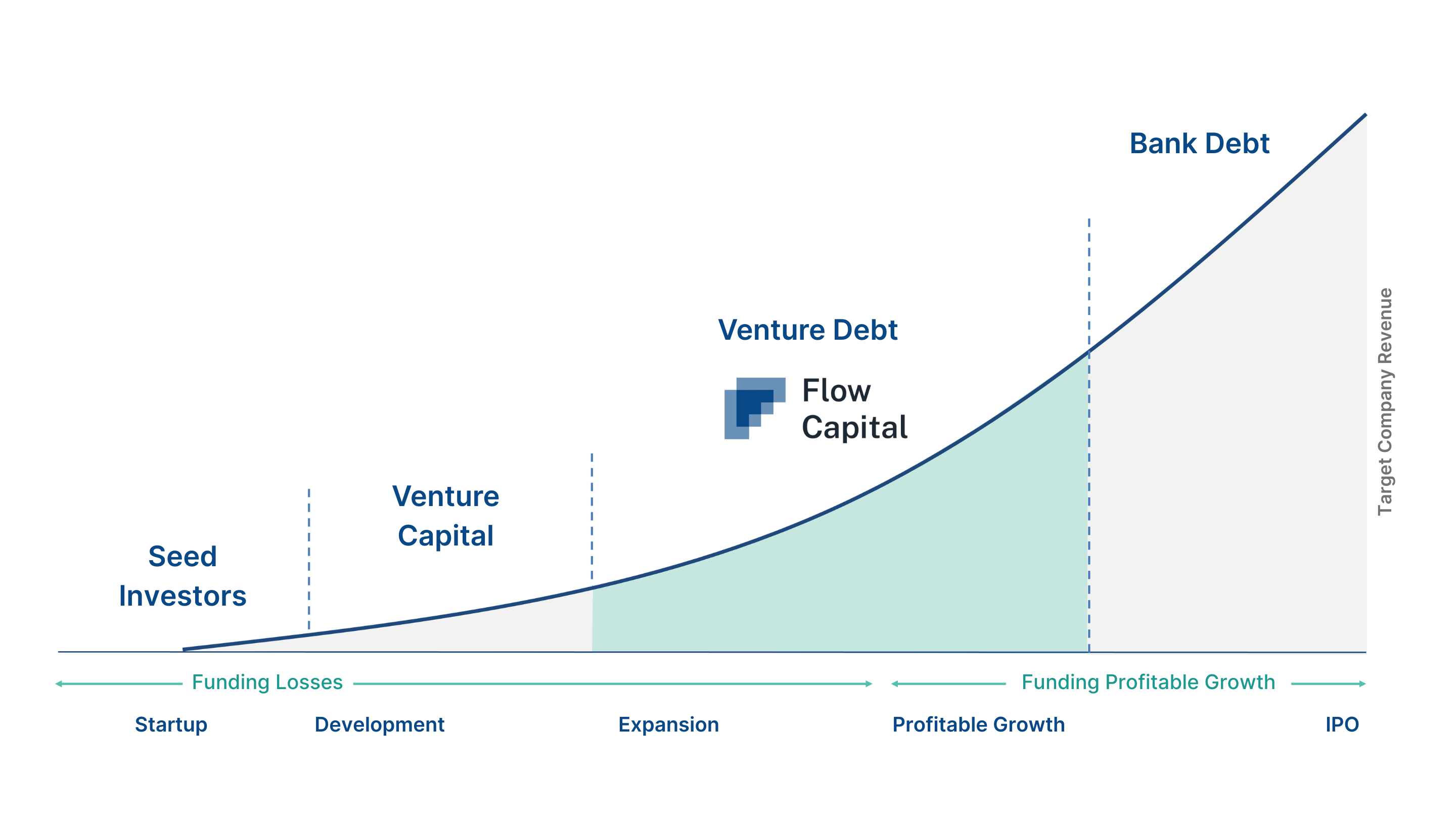

Let’s look at the funding landscape:

Warrants place venture debt between the low risk of a bank loan and the high dilution of a VC round.

The amount of potential dilution is defined by the warrant coverage, expressed as a percentage of the total loan amount. Typical coverage ranges from 5% to 30%, depending on the risk of the deal.

Here’s a simple example:

This means the lender receives a warrant giving them the right to purchase $400,000 worth of your company’s stock.

The good news? This does not mean you give up $400,000 of your company. The lender must still pay the $400,000 to exercise the warrant and buy the shares. If exercised, this warrant typically translates to just 1–2% of total equity dilution. It’s a small slice of ownership, not a controlling stake.

The strike price is the price per share the lender will pay if they decide to exercise the warrant. A lower strike price is better for the lender, as it creates more potential profit.

There are three common ways to set the price:

While warrants represent potential dilution, they offer a few benefits:

For founders, the main risk is straightforward:

For lenders, the risks are greater. Warrants have a finite life, offer no voting rights, pay no dividends, and can expire worthless if the company’s value doesn’t increase past the strike price.

1. Can I negotiate the warrant coverage on my loan?

Yes. While lenders often start with a standard range, coverage is negotiable, especially if you have multiple term sheets, strong financial metrics, or a recent funding round that reduces perceived risk. You can push for lower coverage, a shorter warrant term, or alternative structures like a success fee to reduce potential dilution.

2. What happens to warrants if my company is acquired before they’re exercised?

In most cases, warrants either convert into shares before the sale or are “cash-settled,” meaning the lender receives the value they would have earned had they exercised. How this plays out depends on the warrant agreement, so review it carefully to understand if you’ll need to account for this payout during M&A negotiations.

3. Can warrants be repurchased or cancelled after the loan is repaid?

Sometimes. Some lenders will agree to cancel or sell back unexercised warrants if you repay the loan early or after a set period. This typically requires a negotiated buyback price. If reducing future dilution is a priority, it’s worth discussing this option when structuring the deal.